Karen Reay sat quietly in the back of her high school class, staring in disbelief at a page of search results. She had finally worked up the courage to Google her parents’ names, something she had dreaded for most of her life. While she had been suspicious of what she would find, it didn’t detract from the shock and horror she felt after discovering the dark secret her guardians had tried to shield her from: Her parents are murderers.

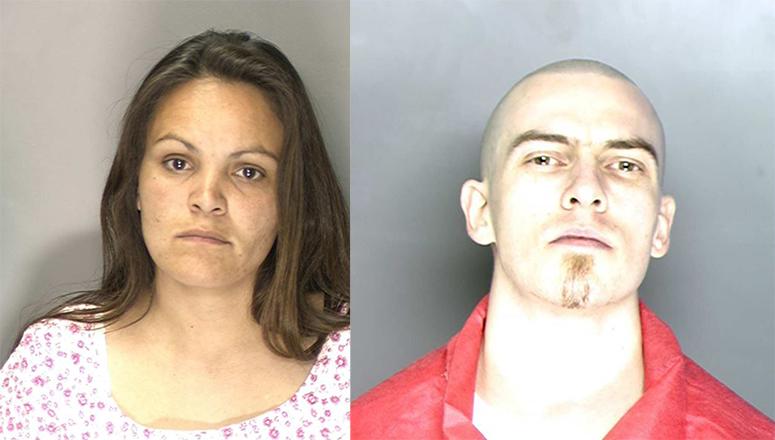

Now a 20-year-old student at American River College, Reay had been born on the lam in January 1995, while her parents were deep in hiding from police. Less than two years before her birth, her parents, Travis and Nettie Reay, had brutally murdered their friend, Angel Evonn Dixon, in a field near the Sacramento International Airport.

“I still don’t believe they could have done it, but they have to have done it. It’s like a nightmare for me,” Reay said. “They’re my parents. I love them, but I don’t know anything about them. And that scares me the most.”

Reay, who lost her parents at age two after they were convicted, had grown up knowing they were in prison. But her paternal aunt, who she calls “mom,” would shy away from telling Reay the details of her parents incarceration, saying only that she didn’t believe Travis was guilty.

(Story continues below)

She received similar treatment from her maternal relatives, who blamed Travis for Nettie’s role in the murder, claiming he was abusive.

It wasn’t until high school that Reay began to search for answers on her own — and discovered why she had grown up only knowing her parents from behind bars.

“Deep in my heart, I kind of knew. People don’t go away forever for nothing,” she said.

But her suspicions didn’t make learning the truth easier.

After a quick search online, Reay found court testimony and articles detailing every horrific aspect, from the killing to the accusations her parents lobbed at one another during the trial.

“I couldn’t read it all. I was just like, ‘No way.’ And I cried. I didn’t tell anybody for a while.”

Court records state that on Aug. 16, 1993, Travis accused Dixon, who was visiting the couple at their home, of using drugs in front of his young nephew. He kicked her out of the house, but then sent a friend, Scott DeGraff, to bring her back. Once she returned, Travis locked the door.

Travis then handcuffed and beat Dixon, with the help of his then-girlfriend, Nettie.

DeGraff, who was given immunity for his testimony, told investigators that Travis immediately feared retaliation for the beating, as Dixon was associated with the Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang, according to court testimony. He told DeGraff that in order to avoid retaliation, they needed to leave the area.

Travis, Nettie and DeGraff loaded Dixon into a car, driving her to an isolated area by the airport.

They stabbed Dixon over 50 times before returning to the car, leaving her to die in a safflower field.

However, Dixon wasn’t dead yet. She pulled herself toward DeGraff, who was waiting by the car, and begged him for help.

DeGraff responded that he did not “want anything to do with it.”

“Apparently one of them went back and finished it off,” Reay said, before becoming overwhelmed by emotion.

Dixon’s body was found the next day. She was 20 years old.

Approximately three years after the murder, the Sacramento County Sheriff’s Department received a tip from an anonymous caller asserting that Travis and Nettie were responsible for the crime. When interviewed, Nettie, who also implicated DeGraff, admitted her role, but claimed that the abuse she suffered at the hands of Travis had left her with no choice but to follow his orders and participate in the gruesome murder.

Nettie’s defense team called expert witness Linda Barnard, PhD, a licensed marriage and family counselor, to testify that Nettie displayed the symptoms of Battered Women’s Syndrome, now known as Intimate Partner Battering and it’s effects.

Twenty years later, Barnard still has strong feelings about the trial. She stands firm in her opinion that Nettie was not responsible for her actions that night.

“My opinion of the case was that she was coerced into the behavior. But because the law doesn’t allow you to use coercion in a murder case, you can’t use coercion as a defense against murder,” Barnard said.

On Oct. 14, 1998, just before Reay’s third birthday, Travis and Nettie were found guilty of first and second degree murder, respectively. Nettie was sentenced to 15 years to life, while Travis was given a sentence of 25 years to life.

(Story continues below)

Reay became a ward of the state, and the subject of a custody battle between her mother’s Native American Tribe, the Sioux, and her father’s family. Her paternal aunt was awarded custody.

Reay’s aunt raised her alongside her cousins, whom she shares a close, sibling-like bond with. Living with her aunt provided a much-needed source of stability.

“I know her as my mother because she’s the only mom that I know,” Reay said.

But as a child, Reay wanted nothing more than to be with her parents.

“For birthdays, for Christmas, all I wanted was them,” she said.

Reay said she understands why her family was not forthcoming with the details of her parent’s incarceration.

“I felt like my whole life was half a lie,” Reay said. “But then the other part of me felt like, well, it’s not like they could have just blatantly told me at six years old.”

As a teenager, it was difficult to process what she had learned of her past — To reconcile the gentle father she had looked forward to visiting with the man described in court documents as a violent, controlling killer.

“To me, my father has just been the gentle dad. He’s always made me laugh, and made me coffee and fed me candy bars when he wasn’t supposed to, when I would visit him,” Reay said.

On the surface, Reay’s relationship with her parents sounds almost typical: they fight, they make up, and both mother and father dote on their daughter. But Reay knows that the relationship is limited severely by her parent’s incarceration.

“They always ask me ‘You’re a photographer, why don’t you send us any pictures?’ And it’s like, ‘I don’t write you for a reason. It’s so hard. What am I going to tell you? I’ve told you the same thing my whole life: I’m going to school, this is what I love, this is the guy I’m seeing, this is my favorite movie.’ It’s the same stuff all the time,” Reay said. “They make me feel bad that I don’t write them, but it’s like, how am I supposed to feel bad when you messed up? You left me here. Both of you.”

The chances of Reay ever experiencing a relationship with her parents outside the confines of a prison are slim.

Nettie was recently granted parole by the state parole board, but was denied release by Gov. Jerry Brown, who uses his power to deny parole far more sparingly than his predecessors.

Brown felt compelled to write about his decision, stating that while Nettie had made efforts to improve herself in prison, including earning her high school diploma and completing vocational programs, her crime was “brutal and inexplicable,” and that her actions “evidenced a cruel and callous disregard for human suffering.”

While Reay has struggled to accept what her parents are incarcerated for, she’s never broached the subject with either of them.

“I’ll never bring it up. I don’t know why, I’m just too scared. Why would I ask a murderer if they murdered somebody? And they’re my parents? For them to say yes would just … I would run away. I’d collapse and die. That’s insane.”

Reay moved out of her aunt’s home at 17, seeking more control, and was taken in by the family of a high school friend, where she met her now-boyfriend, Rick Silva.

It wasn’t long until Reay confided in Silva, opening up about her past.

“She wears her emotions on her sleeve,” Silva said. “I could tell she was a part of something very traumatic, so I knew it had to be true.”

But for years, Reay felt isolated and alone.

While numerous resources exist for victims of violent crimes and their families, children of incarcerated parents are often left without help, forced to find ways to cope on their own.

“I think there’s a lot of stigma for children whose parents are convicted of murder,” said Barnard. “The kids get lost in the shuffle. They usually end up in the system, as a ward of the court, and many of them end up with their own problems, because they’re products of the system instead of products of a loving family.”

According to the New York Initiative for Children of Incarcerated Parents, “more than 2.7 million children in the U.S. have an incarcerated parent and approximately 10 million children have experienced parental incarceration at some point in their lives.” Additionally, “Separation due to a parent’s incarceration can be as painful as other forms of parental loss and can be even more complicated because of the stigma, ambiguity, and lack of social support and compassion that accompanies it.”

(Story continues below)

Parental incarceration is commonly recognized as an “adverse childhood experience” or ACE: a term popularized by a study of the same name performed by the Centers for Disease Control and Kaiser Permanente in the 1990s, which measured the long term health and social impacts of traumatic childhood experiences.

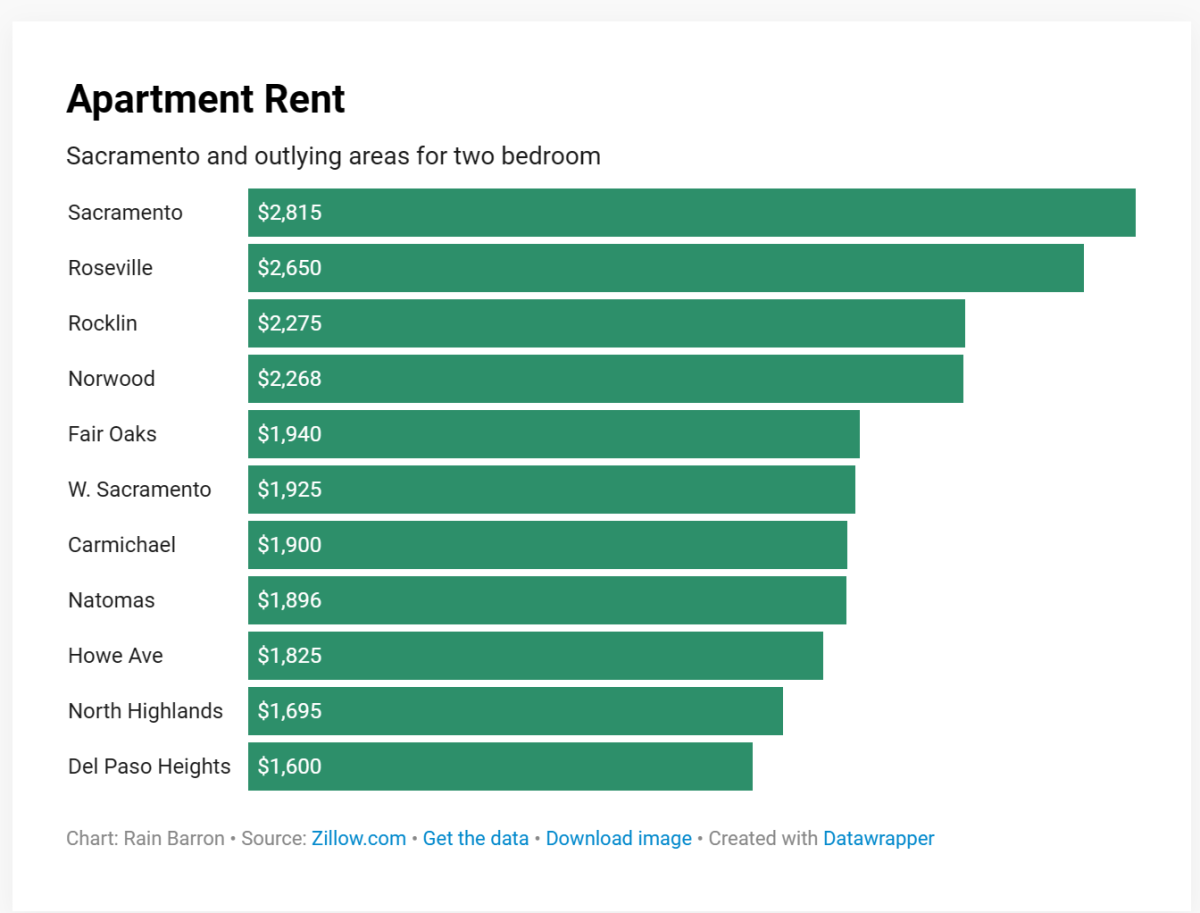

The New York Initiative for Children of Incarcerated Parents adds that visiting incarcerated parents is critical (in most cases) to the well-being of the child, but visits can be difficult due to distance and the costs associated with traveling.

While Reay was somewhat fortunate in her ability to see her parents regularly, the visits themselves were often difficult for her.

“They talk about movies and music and stuff like that and ask me if I like it, because they listen to the radio. And I’ll tell them about today’s technology and what they’re missing out on. But it just feels like the same sentence over and over again because they’re not here with me to see any of it,” Reay said.

Barnard said that the psychological effects of having an incarcerated parent can be devastating.

“You’re never going to see your mother again except in prison, when you visit the prison, in the confines of the prison. You’re never going to have a normal kind of life,” Barnard said.

But Reay doesn’t look at it that way. She had decided, early on, that she would dictate the kind of life she lived, and found motivation in her experiences with her parents.

“I wanted to be better than them. Both of them, put together,” she said.

Reay’s desire to move forward has been aided by discovering photography while at American River College — A passion she pours all of her energy into, often waking up before 6 a.m. to catch the bus to school, spending hours on campus and scheduling shoots on the weekends.

(Story continues below)

Silva has seen it first hand in the two years he’s dated Reay, and is continually impressed by her determination.

“She’s probably the most driven person that I know,” said Silva. “I don’t know anyone that will scrape and scrounge and will get on the bus everyday, and will get up early, and do it all by themselves.”

Reay now hopes to start a support group for children of incarcerated parents.

While her main objective is to help an often overlooked group find support and healing, she also hopes to simply meet others who have experienced situations similar to hers.

“I feel like I could relate and find a little bit more peace, because I’m not alone, and somebody else understands, and that person can’t tell me to just get over it and to move on,” she said. “Because you can’t.”

But considering where she is now, Reay said that given the chance, she wouldn’t change anything.

“Not a damn thing, no matter how much pain it’s caused me. Nothing.”

To read more about expert witness Linda Barnard’s account of the trial of Travis and Nettie Reay, click here.

Kiss • Sep 13, 2018 at 5:50 pm

Knowing Karen and who she is is inspiring. This is so heartbreaking but wow, Karen you are so amazing despite your circumstances. I really am in awe of the way you have overcome the dark and I’m inspired by you everyday.

Maria • Jun 27, 2018 at 10:30 am

No offense BUT I grew up around her family. Her mom was ANYTHING but a good mom, drugs, men in and out, and a terrible environment for a animal, let alone a little girl. A abusive older brother, the list goes on. What happened to Angel was horrible, and I am heart broken that that happened to her. The monsters that did this should not right where they are…

Deanna • May 19, 2015 at 10:13 am

I really think it is shameful that AR Current chose to publish this article. You obviously never considered what this article would do to the victims family! This article has caused Angel’s family much grief. Shame on you American River Current!!

Deanna • May 15, 2015 at 7:46 am

Her parents are evil. In my opinion they should spend the rest of their lives in prison. Society should be very affraid when either one of them get out. I am sorry for Karen having been born to these two monsters but a blessing she was not raised by them ….I have a feeling her outlook on life would be completly different (in a bad way). Regarding the victim, Angel Evonn Dixon…who is she and what impact did Nettie, Scott and Travis’ decision have on her family? Since you decided to put forward this article, let’s get the facts about the victim, Angel. She was not a drug addict like was portrayed by Nettie and Travis. She also was 20 years old and a mother of two little boys when she was murdered, she had NO affiliation to the Hell’s Angels and she was a beautiful person inside and out. I believe Angel was murdered because of jealousy. Nettie had a relationship with Scott prior to her relationship with Travis so there was no trust in that relationship. Angel was in the wrong place at the wrong time with the wrong people, she thought were her friends. Angel, her two babies and Karen Raychel are the victims of Nettie, Travis and Scott’s (or lack of) actions. Angels babies grew up without their Mother too. Their Father died shortly after Angel was murdered., due to health issues so they were raised by family.

andriA furman • May 7, 2015 at 8:06 pm

Cousin i had no idea. Your a strong woman n you will get threw this like u been. i love you. Keep ur head held high.

chastity kuhn • May 7, 2015 at 12:41 pm

Kuzn I love u .. Ur stong really strong ..I don’t no how u do it I couldn’t I miss u