Errors in guidance from counselors frustrate students

Students are frustrated by a seeming increase in mistakes from the counseling office

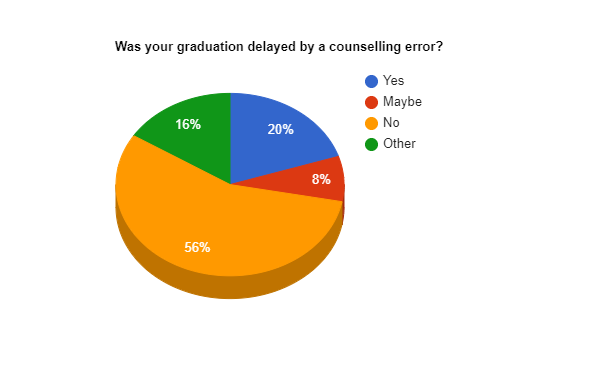

According to a 53-person survey taken by American River College, history major Hunter Farnbach, 20% of students feel their graduation was impeded by counseling errors. (Graphic by Ben Kynaston)

According to a 2018-2019 overview from US News & World Reports, the graduation rate for three-year students at American River College is 27%. Despite the focus within the district and on the school website about prioritizing a speedy, easy degree for students, it seems that the reality is looking a little different for students, especially those who take advantage of the ability to transfer to other schools within the district.

I recently learned that a creative peer of mine, history major Hunter Farnbach, brought a grievance against the ARC counseling department in April. This case represents a frustration that, after breaching the subject of counseling errors in a Zoom classroom, I realized was widely echoed. I’ve seen a lot of frustration among students with the counseling department and its tendency for error.

Personally, I believe that there should be a larger conversation about educating and training counselors on the intricacies of the program rather than sending out counselors who don’t have all the information they need to help students. It makes it harder for students to feel comfortable asking for help, let alone trusting that they’ll be taken care of.

In Farnbach’s case, the student’s six-year journey with the LRCCD was meant to end this semester, only to have him discover in a meeting with his counselor that he had one class credit missing and was ineligible for graduation. This despite the fact that Farnbach had taken precisely the class he was missing—only at a different school.

Farnbach had always focused on graduation as a goal and had worked with counselors for his entire time within the district with that in mind, and not even one counselor had mentioned a problem with his credits.

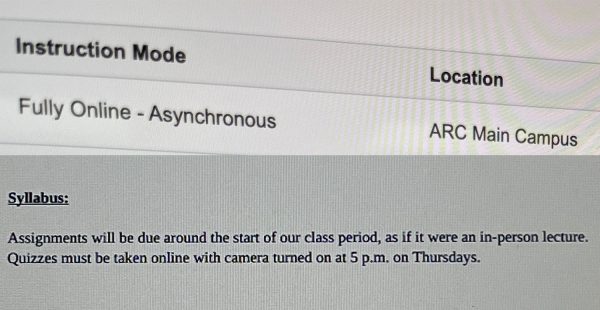

Despite the code for the class being the same between the two catalogs, having the same name and subject matter, his completion of the class did not count because of a breakdown in the credit articulation program that must have left the course out of its consideration. This meant Farnbach must either take the class again or take an equivalent class for the credit.

After his hearing, it was decided he would take the class again but all fees would be waived.

In preparation for this hearing, Farnbach conducted a poll, asking ARC alumni and staff on his Facebook friends list if they had been told while talking about the college that their credits would be transferable throughout the district, and 81% of responding students, alumni and staff said yes.

Students who shared Farnbach’s misfortune with the counseling department left their stories in the survey. Of the eight students who said their graduation was delayed by a counseling error, six were students at multiple institutions, in many of those cases, meeting similar credit articulation issues.

To me this is the biggest issue, if students are being encouraged to take classes at all the colleges in the district to get their credits squared away, promising they can use them at any institution, they should be able to attain those credits. If it’s not already designed to transfer credits between schools, because they’ve already promised that that was the case, they should take a look at their catalog and pay a little closer attention to how class pathways and credit articulation are designed, specifically in terms of student success.

In an online class with the staff of the newspaper, a few of my peers agreed that the counseling department’s unreliability was getting in the way of their educational experience, slowing their graduation and putting more stumbling blocks in front of them on the way to their goals, rather than offering proper, trustworthy guidance.

In my opinion, the idea that the only place to go for help at school regarding these issues can’t necessarily be trusted is a cause for concern, and the decision to force Farnbach to take the class again rather than simply granting him the credits he needs doesn’t sit well with me either. I can only hope this story makes more people curious about the way institutions are designed and who benefits from them, in this case, and on a larger scale.

Hunter Farnbach • Jul 13, 2022 at 2:23 pm

An update a year later:

After completing the necessary class in the fall and petitioning to graduate again in the winter, I received an email 6 months after saying I still needed yet another class.

ARC counseling needs to do better.