Pandemic stress creates academic integrity issues

Stressed students cheat, so professors have to create un-cheatable exams

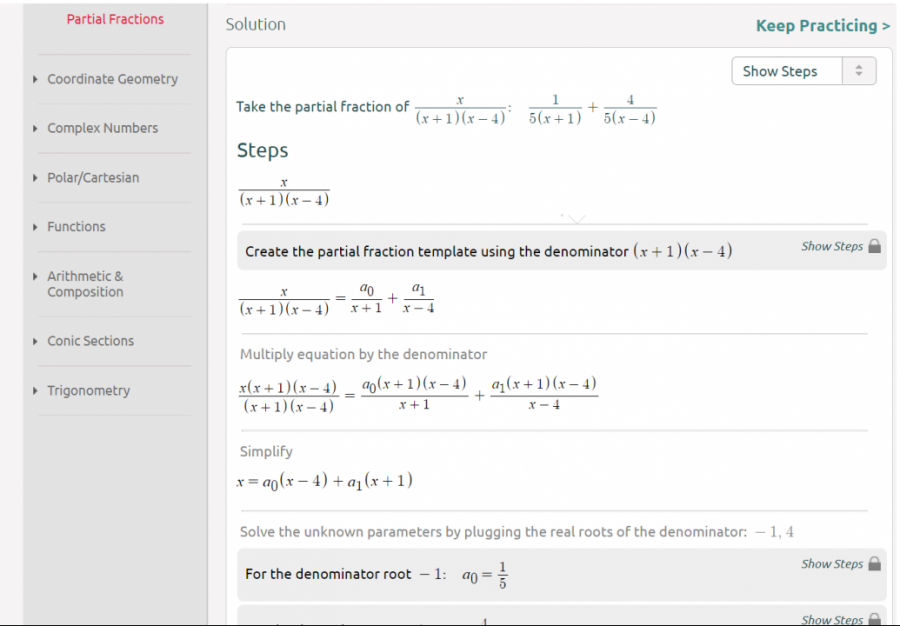

According to math professor Matt Mitchell, at American River College, students use websites such as Symbolab to cheat on their exams. Unfortunately, it’s difficult to sort out the honest and dishonest students. (Screenshot via Symbolab)

Students under pressure are more likely to cheat. That’s what Elizabeth Huffman, political science professor at Cosumnes River College says. As this pandemic weighs down on students and professors alike, maintaining high standards of academic integrity becomes more difficult.

During Huffman’s Feb. 2 workshop on academic integrity, she described how many of her students are now facing problems such as supporting their parents who had lost jobs, caring for sick family members, providing childcare or helping their younger siblings with their own schoolwork.

Professors have also been under extra pressure. With very little warning, professors had to adapt their classes for online learning.

According to Huffman, professors simply didn’t have the time to rework their courses. To combat cheating in an online environment, professors have to create uncheatable exams.

Matt Mitchell, math professor at American River College, says he has had a lot of problems with students cheating on his math exams. His final exam for Math 372 in the fall of 2020 was particularly problematic.

This exam-focused on a process called “decomposing partial fractions.” According to Mitchell, this is a very involved process that requires a solid understanding of algebra.

In a class of 30 students, Mitchell would expect about five As on this test. For his fall 2020 class, 29 students out of 32 received As.

“Some students who got perfect scores had done zero homework for this section, and thus had no practice,” Mitchell said.

When correcting the finals, Mitchell noticed that several students used an overly complicated method to answer one of the questions. He discovered that if he plugged that question into Symbolab, a website dedicated to answering math problems, the site gave the correct answer with the same overly complicated method shown.

As a result, Mitchell believes that many of the students in his class may have cheated, but he has no way of telling who the honest students were.

Mitchell didn’t use a remote proctoring program such as Proctorio because he didn’t believe it would help keep students honest. Proctorio accesses the student’s device camera and microphone to record the student taking the test. He believed it would punish the honest students and the dishonest students would simply cheat on their phones anyway.

Huffman doesn’t believe Proctorio is the answer either. According to Huffman, programs such as Proctorio are detrimental to students because they create an environment where students don’t feel trusted.

Not only do programs like Proctorio not work well with many disabled students, but Black students often don’t show up well on Proctorio’s camera, according to Huffman. As a result, Black students often must shine bright lights on themselves to take an exam.

Michael Sweet, biology professor at ARC, doesn’t use Proctorio for his non-major classes either. Instead, he adapted his classes to disincentivize cheating. Students can use notes and the internet to take their tests.

“Students can even collaborate, so cheaters have no advantage over honest students because everything is allowed,” Sweet said.

These online exams aren’t worth very many points, however. Instead, Sweet has greatly increased the homework and given other incentives to pay attention in class.

Sweet imbeds assignments in the video classes, asking students to email the answer to him after class. Students who skip class or aren’t paying attention miss out on these assignments.

Some professors, such as Dale Hoffman, ARC anthropology professor, have always worked to make their exams cheat-proof, so this pandemic didn’t change much.

“Maybe because I work in a prison, I always think about how someone could cheat on my exams,” Hoffman said.

Hoffman believes the secret to making a “cheat-proof” exam lies in making the exam part of the learning process, instead of a way to assess student ability. Hoffman has open book tests, encourages students to re-do work to bring up their grades, and encourages students to ask questions about the test prior to taking it. According to Hoffman, this takes off the pressure, so students are less incentivized to cheat.

Huffman recommends students take the pressure off themselves by taking fewer classes so they don’t get overwhelmed.

Students who feel pressured this semester are encouraged to find tutors to help them through their classes.

“Scale back your expectations of yourself so you can act with integrity,” Huffman said.

Editors Note: This story has been updated to reflect that American River College Math Professor Matt Mitchell does not believe that a majority of the students in his classes cheated on their exams, and instead he expresses that he just has no way of knowing who did or did not cheat, though he speculates that some students may have cheated, indicated to him by his test scores in the spring semester of 2021. The Current regrets any misinformation or confusion on this issue.

Michael Sweet • May 18, 2021 at 12:51 pm

I agree that it’s critically important to find ways to reward the many hard-working students who are acting honestly. Professor Mitchell’s suggestion to find safe ways to increase in-person testing are right on.

Matt Mitchell • May 16, 2021 at 11:00 am

It is not my belief that most of my students cheated, but undoubtedly some have. There are other explanations for the large number of A’s – for example, I have no choice but to make exams open book and open notes since each student is taking the test in their home. Those are notes that students wouldn’t have in front of them in a classroom… so that’s certainly going to have an affect on the number of high marks on an exam like this. But there is no question that a handful of students, clearly those who did no homework, used a simple Google search to find the correct answers to some of these challenging problems.

The “take away” from all of this, in my opinion, is that whether Covid makes a robust return or we end up faced with a different pandemic, a great deal of energy should be put into finding a way to conduct in-person testing, whether that’s splitting a class of 36 into three groups of 12 that are distanced, masked and separated by plexiglass or whatever. Without in-person testing, it’s difficult to know which high grades represent mastery and which don’t, and I find that very unfortunate for the students who are holding themselves to an honest standard. Bravo to those who do. I think that choice will pay dividends in many ways.